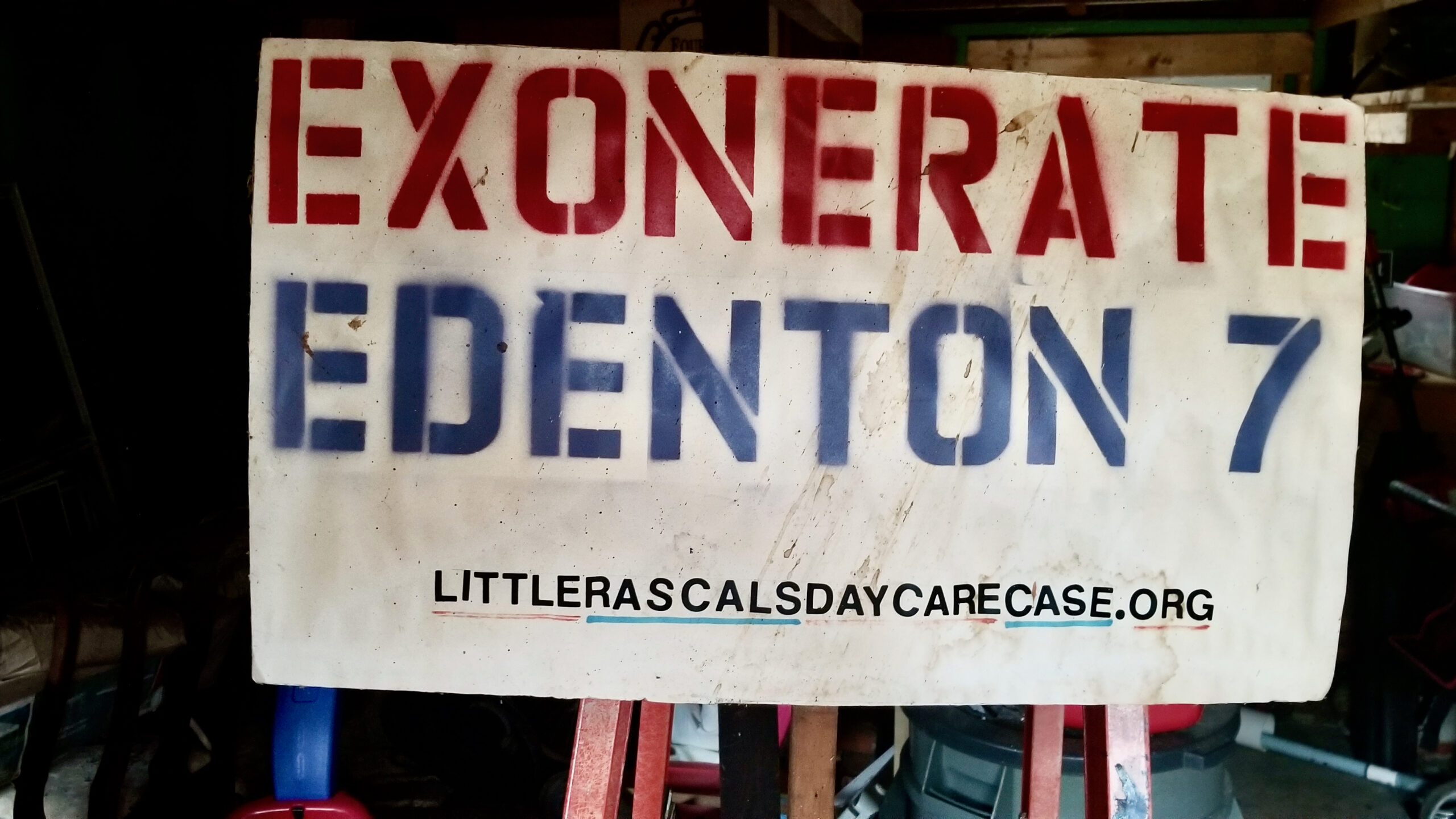

Rascals case in brief

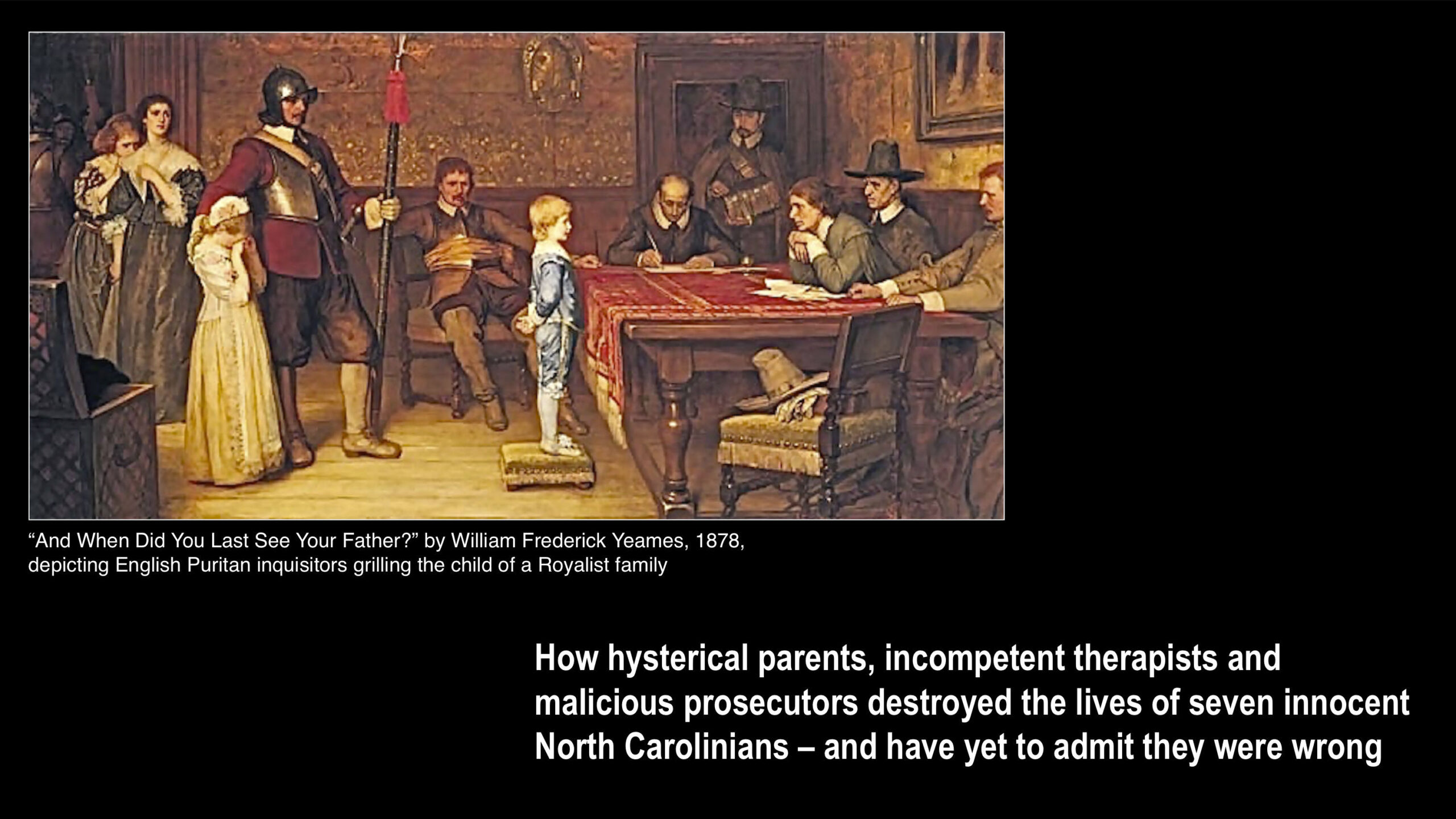

In the beginning, in 1989, more than 90 children at the Little Rascals Day Care Center in Edenton, North Carolina, accused a total of 20 adults with 429 instances of sexual abuse over a three-year period. It may have all begun with one parent’s complaint about punishment given her child.

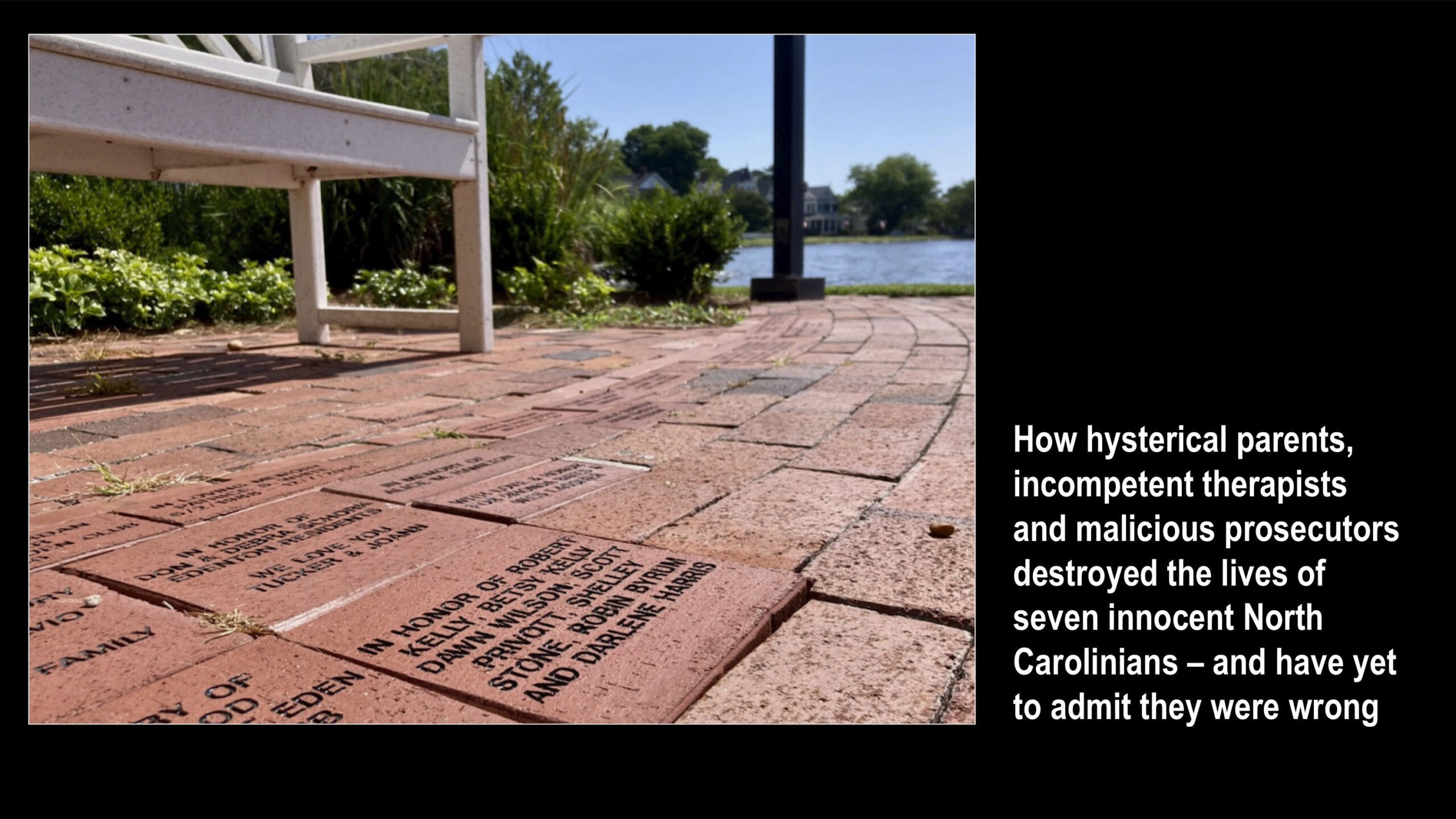

Among the alleged perpetrators: the sheriff and mayor. But prosecutors would charge only Robin Byrum, Darlene Harris, Elizabeth “Betsy” Kelly, Robert “Bob” Kelly, Willard Scott Privott, Shelley Stone and Dawn Wilson – the Edenton 7.

Along with sodomy and beatings, allegations included a baby killed with a handgun, a child being hung upside down from a tree and being set on fire and countless other fantastic incidents involving spaceships, hot air balloons, pirate ships and trained sharks.

By the time prosecutors dropped the last charges in 1997, Little Rascals had become North Carolina’s longest and most costly criminal trial. Prosecutors kept defendants jailed in hopes at least one would turn against their supposed co-conspirators. Remarkably, none did. Another shameful record: Five defendants had to wait longer to face their accusers in court than anyone else in North Carolina history.

Between 1991 and 1997, Ofra Bikel produced three extraordinary episodes on the Little Rascals case for the PBS series “Frontline.” Although “Innocence Lost” did not deter prosecutors, it exposed their tactics and fostered nationwide skepticism and dismay.

With each passing year, the absurdity of the Little Rascals charges has become more obvious. But no admission of error has ever come from prosecutors, police, interviewers or parents. This site is devoted to the issues raised by this case.

On Facebook

Click for earlier Facebook posts archived on this site

Click to go to

Today’s random selection from the Little Rascals Day Care archives….

Click for earlier Facebook posts archived on this site

Click to go to

Today’s random selection from the Little Rascals Day Care archives….

‘A good day for justice’ in Texas – why not in NC?

cbsnews.com

Charles Sebesta

Feb. 13, 2016

“The disciplinary board of the Texas State Bar on Monday affirmed the agency’s decision to disbar Charles Sebesta, the former prosecutor who oversaw the wrongful death sentence of Anthony Graves.

“Graves, who spent 18 years in prison, including 12 on death row, for a fiery multiple murder he did not commit… had asked the Bar to hold Sebesta accountable for withholding critical evidence of his innocence.

“ ‘The bar stepped in to say that’s not the way our criminal justice system should work,’ Graves said. ‘This is a good day for justice.’ ”

– From “State Bar board affirms disbarment of prosecutor who sent innocent man to death row” by Brandi Grissom in the Dallas Morning News (Feb. 8)

Legal scholar Jonathan Turley notes that “Sebesta’s conduct was shocking but remains a relatively rare example of prosecutors being held accountable in such cases of prosecutorial abuse.”

Although the Texas Bar displayed little eagerness to bring a prosecutor to justice – and disbarment is a petty consequence indeed for the enormity of Sebesta’s malfeasance – its response seems darn near heroic compared with the shameful vindictiveness we have come to expect from the North Carolina Bar.

![]()

When skepticism is set aside for outrage

July 13, 2012

July 13, 2012

“It is painful to admit this, but when the McMartin story first hit the news, the two of us, independently, were inclined to believe that the preschool teachers were guilty. Not knowing the details of the allegations, we mindlessly accepted the ‘where there’s smoke, there’s fire’ cliché; as scientists, we should have known better.

“When, months after the trial ended, the full story came out – about the emotionally disturbed mother who made the first accusation and whose charges became crazier and crazier until even the prosecution stopped paying attention to her; about how the children had been coerced over many months to ‘tell’ by zealous social workers on a moral crusade; about how the children’s stories became increasingly outlandish – we felt foolish and embarrassed that we had sacrificed our scientific skepticism on the altar of outrage.

“But our dissonance is nothing compared with that of the people who were personally involved in or who took a public stand, including the many psychotherapists, psychiatrists and social workers who consider themselves skilled clinicians and advocates for children’s rights.

– From “Mistakes Were Made (But Not by Me)” by Carol Tavris and Elliot Aronson (2007)

Of course, not everyone who “mindlessly accepted the ‘where there’s smoke, there’s fire’ cliché’ ” has recovered his misplaced scientific skepticism.

Who killed the ritual abuse day care panic?

April 9, 2012

April 9, 2012

“Where do epidemics go when they die?…. Have all the sadistic pedophiles closed down their day-care centers?”

– From “Mistakes Were Made (But Not by Me)” by Carol Tavris and Elliot Aronson

I asked Mary de Young, author of “The Day Care Ritual Abuse Moral Panic,” whether this epidemic might have gasped its last in Edenton as a result of “Innocence Lost.”

“Ofra Bikel certainly pounded a nail in its coffin,” De Young said. “Her excellent work on the Little Rascals case appeared after the last day care ritual abuse case was prosecuted, but she created a reason to be profoundly skeptical of all the cases that came before.

“I would give a lot of credit to Debbie Nathan (Village Voice) and Dorothy Rabinowitz (Wall Street Journal) for bringing an end to this craziness, but to be honest I think the moral panic really collapsed under its own weight – i.e., it was impossible to sustain these allegations in the absence of evidence, as well as to sustain the suspended disbelief that was required.”

Leading questions, not spontaneity, marked interviews

May 4, 2012

May 4, 2012

“Written reports that contain statements such as ‘The child said that Mr. Bob told them secrets’ are meaningless.

“We need to know whether this was a spontaneous remark, whether this was prompted by an open-ended question (e.g., “What did Mr. Bob tell you?”), or whether this is merely the interviewer’s memory of the gist of a conversation in which the interviewer asked, ‘Did Mr. Bob ask you to keep secrets?’ and the child reluctantly may have replied, ‘Yes.’

“Some summaries of the interviews are written in such a way as to make one believe that children made spontaneous and detailed statements about sexual abuse. However in the few instances where we have transcripts of other interviews, it is clear that the child only responded ‘yes’ or ‘no’ to a barrage of leading questions.”

– From “Jeopardy in the Courtroom: A Scientific Analysis of Children’s

Testimony” by Stephen J. Ceci and Maggie Bruck (1995)

0 CommentsComment on Facebook